Science fiction is a genre that I have delved into only very infrequently in my life. I read a fair amount of it in childhood, then almost none for a few decades, then more recently I read the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies of the less-than-novel-length science fiction voted the best of all time.

After the time period covered by those anthologies, awards for the best science fiction (called the “Nebula Awards”) have continued to be presented on a yearly basis, with the winning stories anthologized usually about a year later.

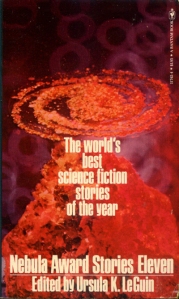

The first such anthology after the broader Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies came out in 1977 as Nebula Award Stories Eleven. It is a collection of the 1975 winners. It does not include the winning novel, though it does include an excerpt from it as its own self-contained story. It also includes the winning novella, the winning novelette, the winning short story, three of the seven runners-up in the short story category, and two essays about science fiction.

The anthology’s first story is Catch that Zeppelin! by Fritz Leiber, the 1975 Nebula winner in the short story category. It’s an interesting “parallel universe” tale. A man walking through New York City suddenly falls into a sort of reverie where he’s convinced he’s a different man at a different time—Adolph Hitler in 1937. (His identity is not fully revealed until near the end of the story, but that’s not much of a spoiler because it is strongly hinted at from very early.)

This Hitler is not a dictator, though, but a high official doing some kind of negotiations in the U.S. regarding zeppelins. Germany is a dominant economic power, with the U.S. as apparently at most a junior partner, in a world enjoying a sustained period of peace.

His son, whom he meets for lunch, is an academic historian who specializes in identifying key historical events that drastically changed the development of the future.

This gimmick allows the author to attribute the contrast between the 1937 of this story and what we recognize as the real 1937 to a handful of historical differences. The most significant is probably that Edison married Madame Curie (who of course therefore wasn’t Madame “Curie”) and that they had a son who was even more brilliant than either of them, and as a result of the work of these three geniuses cars were run by an ultra-efficient battery rather than gasoline and zeppelins were powered by synthetic helium rather than hydrogen, with these and various other technological advances providing an enormous economic boom without accompanying problems like pollution.

Other important differences include that Germany was definitively defeated in World War I rather than signing an armistice to end the war early, which paradoxically was highly beneficial to it since the Allies were much more generous in the conditions they imposed on their defeated foe, and there was not the same internal strife based on a myth of German leadership selling out and stabbing its military in the back by not letting them fight on and win.

It’s not just Germany as a whole that was not so embittered, but Hitler himself. He’s a reasonably content, peaceful, sane person. He and Germany experienced military defeat and certainly suffered thereby, but the degree of humiliation was considerably less.

That lessening of humiliation also meant a lessening of scapegoating. This Hitler manifests not the racism of a Nazi but at most the mild racism of the average 21st century white American.

Next up is End Game by Joe Haldeman, an excerpt from his The Forever War, which won the award for best novel.

The setting is several centuries in the future, in the midst of a war that started in the late 20th century and gives no indication of ending any time soon. It started as soon as people from Earth commenced star travel, as they came up against a hostile force of “Taurans.” Not much is known about the Taurans, as one has never been captured alive and no way of communicating with them has ever been discovered. But apparently the war is fairly evenly matched, as neither side has gained a big enough advantage to finally defeat the other. They just send soldiers to far flung planets in distant galaxies to kill each other.

Some of it reads like any war story. (The bulk of the story is about some Earth people on a distant base in the middle of nowhere who are attacked by a force of Taurans.) The weapons are different and all that, but much of it would overlap with an account of a World War II battle, or I suppose a Punic War battle. The author even introduces a gimmick that results in the armies fighting each other part of the time with bows and arrows and swords and the like.

How does the future differ, besides that it involves a seemingly endless extraterrestrial war? For one thing, virtually everyone is homosexual. Apparently once non-sexual reproduction was perfected, reproductive sex or sex that risked reproduction was frowned on and gradually died out under social pressure.

There is time travel, at least forward. The protagonist (and narrator), for instance, is from the 20th century.

Evidently Taurans time travel in similar fashion. In fact, a lot of the weapons and such are copied from each other. So each side has whatever they’ve developed to that point, and most or all of what the other side has developed until very recently. One consequence of this is that when you go into battle you have no way of knowing in advance what time period the opposing force is from, and you may find yourself battling soldiers with technology decades or centuries ahead or behind your own (which results in a slaughter).

One of the less convincing details is the narrator’s claim that he and other long term soldiers who time traveled will never be permitted to leave the service because the accumulated back pay and retirement benefits and such from several centuries would basically bankrupt the government. (That sounds more like a joke from Sleeper.)

It’s a moderately interesting story, more so in its descriptions of the different reality of the future than in its conventional war story elements. I liked one of the twists at the end in particular, in part because I speculated about it from early in the story. I don’t know that you can say it’s really telegraphed, but it’s something I thought would be interesting if it was what was really going on, and it turns out it was.

The book then takes a break from the stories for an essay by Peter Nicholls entitled 1975: The Year in Science Fiction, or Let’s Hear It for the Decline and Fall of the Science Fiction Empire. I didn’t find it particularly valuable. Nicholls’s metaphor of contemporary science fiction somehow being like an aging empire collapsing into chaos on its fringes while remaining somewhat vibrant at its center is strained to begin with, and torturously trying to sustain it for page after page doesn’t help.

Home is the Hangman by Roger Zelazny, the winner in the novella category, is one of the better science fiction tales I’ve read. Structured as a mystery, it is the story of a sort of freelance detective on the trail of a possibly murderous robot or android-type creature.

The “Hangman” was an invention of some years earlier, an invention that held early promise but ultimately failed, or seemed to. In a pioneering attempt at artificial intelligence, a robot brain was built not in conventional computer fashion but as close as possible to the way the human brain is structured and functions. Multiple programmers then provided the content for this artificial brain by connecting their own brains to it. It was then placed in a robot body, and the robot trained as a pseudo-astronaut for unmanned missions into deep space.

There was speculation and intriguing but inconclusive evidence as to when in its increasing complexity might enable it to develop emergent properties such as consciousness, self-consciousness, the ability to learn new things that go beyond its programming, emotions, a moral sense or conscience, free will, etc. But then it went haywire out in space, suffering what seems to have been the equivalent of a mental breakdown (maybe a form of schizophrenia from having within it the combined contents of the minds of its multiple programmers?) and its spaceship was lost and presumed destroyed.

But now the spaceship has mysteriously returned. By the time it is fished out of the sea where it had plunged, it is unoccupied, but there is reason to think the Hangman was aboard, and further that he may have murderous intentions toward his programmers. The protagonist must track and stop the Hangman before he gets to his potential victims.

This would be a no worse than average mystery even without the science fiction angle, but all the speculative elements about how a creature like this would think and be motivated and such makes it that much more intriguing.

It does have its weaknesses—the dramatic hand-to-hand combat stuff is even sillier than usual, since allegedly this robot has something like ten times the strength of a normal man—but it held my interest throughout, and the ending is mostly satisfying.

Child of All Ages by Phillip James Plauger, one of the runners-up in the short story category, is about a young girl who is in fact not so young. Like the protagonist in one of the better known Twilight Zone episodes, she is locked into her present age. Unlike the guy in the Twilight Zone story though, she can in principle die in ways that aren’t related to the body’s aging or naturally failing in some respect (e.g., accident, suicide, murder, etc.), and she can turn off her immortality and resume aging and eventually die any time she chooses to by ceasing to take the potion she consumes regularly.

This is a solid story that raises plenty of interesting “what would you do if you were in this person’s shoes” thoughts. One wonders, and indeed she is asked in the story, why she has never chosen the option of allowing herself to age through a normal life and die, since frankly her roughly 2,400 year life so far doesn’t sound like it has been very pleasant on the whole (constantly having to invent new backstories for herself and move from family to family, etc.), but her will to live always makes sticking it out a little longer and making due seem better than letting her life end entirely.

At some fairly early point, I suppose, she got used to the way she lives as really the only life she knows, and she’s no more willing to give it up than most of us are willing to give up our lives, which contain their own imperfections, suffering, and challenges that we’ve gotten so used to as to treat as normal.

The second essay of the book is Potential and Actuality in Science Fiction by Vonda N. McIntyre. I liked this considerably more than the Nicholls piece.

McIntyre references a “three stage” theory of science fiction from Joanna Rusk, where the third, most sophisticated and difficult but valuable, stage is the social and psychological consequences of the stories’ new technology and innovations. She contends, and I agree, that all too little science fiction succeeds at this third stage.

As she says, “A tremendous number of far-future stories are set in social systems identical to that of middle America in the mid-fifties.” And it’s not just hack science fiction. One of the things I was most struck by in my earlier reading of the supposedly greatest science fiction stories of all time was this very thing, the way in so many of the stories people behaved like stock B-movie characters from decades ago.

The next story is Shatterday by Harlan Ellison, another of the runners-up in the short story category.

The premise of the story is that a man has somehow split into doubles. He (well, one of the “he’s”) discovers this when he absent-mindedly calls his own house and is startled when he (i.e., his double) answers.

Both versions of the guy decide that it would be intolerable for both to remain in existence, so they each pursue a plan to kill the other.

Initially as a reader my thoughts went to questions like “Is something supernatural really happening or is this just a way to convey roughly what’s going on inside of an insane, schizophrenic person’s mind?,” “If it’s really happening, how did such a thing come about?,” “How would I respond if I found myself in this situation, if somehow I encountered my doppelganger?,” “Why did he/they both immediately jump to the conclusion that the other must be destroyed, and is that a correct conclusion?,” “Is one of them the ‘real’ person and the other not, in some meaningful sense?,” and so on.

But it turns out it’s really not about the scientific or magical way something like this could happen, or the practical or philosophical consequences of it doing so. The intriguing focus instead is on how the two versions of the guy pursue diametrically opposed strategies for eliminating the other. I can’t say much more about it without completely spoiling it, but it’s an interesting take on truly letting your old self go when you realize you need to make radical changes in your life.

The winner in the novelette category (a “novelette” is shorter than a “novella” by the way) is San Diego Lightfoot Sue by Tom Reamy.

This was one of my favorite stories in the collection, though I have to say you have to interpret the science fiction genre very broadly for this to even count as a science fiction story. There are brief suggestions of magic (witchcraft, fortune telling type stuff) at the very beginning and very end, and that’s it. The evidence that anything truly supernatural happens is limited and ambiguous. So it has either a small amount of that fantasy stuff or none, and even if it had a more substantial amount, not everyone would classify such material as science fiction anyway.

Really you could ignore the witchcraft stuff—or treat it as metaphorical or whatever—and you’d lose virtually nothing from the story.

San Diego Lightfoot Sue, set in the 1960s, is the story of John Lee Peacock, an utterly naïve 15 year old who has never left his family’s farm in rural Oklahoma. His father is completely indifferent toward him, as he is toward all his kids. His mother dotes on him and wants what’s best for him, but she and the family are poor, simple, minimally-educated folks who have little to give.

Just before she dies she sets aside what little money she has for John Lee, to enable him to escape into the wider world and seek his fortune. He hops on the first bus he comes across, which happens to be going to Los Angeles.

There John Lee falls in with basically the cast from Lou Reed’s Walk on the Wild Side. Soon he’s living with an interracial couple of queens, and befriends and ultimately falls for a middle-aged ex-prostitute artist whom he poses for nude.

I’ve been thinking about why this story drew me in, and gave me as warm a feeling as it did. Maybe it’s because I sense that Reamy genuinely likes these characters, and thus they become likable to a reader. These are “fringe” people that a large percentage of folks would instinctively condemn as leading immoral lives, but I think 95% of such a reaction is just a matter of going along with common taboo morality without bothering to think it through, and only 5% is substantive and potentially has some justification.

When you look beyond that stuff and examine instead whether these characters treat others with understanding and compassion, manifest integrity, enjoy their lives and get the most out of them without hurting others, refrain from violence, etc., there’s far, far more good than bad in them.

Maybe Reamy’s sympathetic portrayal of these characters stems in part from the fact that—as we learn in the brief editor’s introduction to the story—he lived a version of this story himself. Like John Lee, he too grew up in the middle of nowhere in Oklahoma and then ventured out to Los Angeles, where he eventually spent some time in the porn industry among other things. I’m sure he didn’t start out as naïve as John Lee, but one gets the impression there was considerable overlap. He spent a year and a half in Los Angeles as a youth, and I suspect it was a period he looks back on as exciting, eye-opening, a little scary, and in general a time when he felt very alive and the people and events seemed somehow more important and more interesting than most or all of what came before or after.

I base that in part on my own feelings about the first few years after I left home at age 17, which included some time living in the French Quarter of New Orleans where I knew people not unlike those who populate this story.

There are many elements of this story that made me think and that I’m tempted to comment on, but as it’s just one story out of seven (plus two essays) in this collection, I don’t want to go on too long about it.

By the way, what’s the slang meaning of “lightfoot”? It isn’t explained in the story, Urban Dictionary was no help, and the minimal mentions I found of this story online offer no clues. Does it mean “prostitute”? Does it mean someone who moves around a lot? Does it refer to someone who is “light on their feet” in the sense of being resourceful, quick-thinking, good at getting out of jams, etc.?

The final story in the anthology is Time Deer by Craig Strete, another runner-up in the short story category. At just seven pages, it is by far the shortest piece in the book.

It is the story of an aging Indian man looking back on his life. It is a strongly “pro-Indian” story, celebratory of what it presents as the native way of looking at the world and at life, and condemnatory toward the conventional Western philosophies and lifestyles that basically shunted aside that worldview.

Here too there is little in the way of science fiction, just some religion or spirituality-tinged fantasy, which could easily be interpreted as symbolic or as someone’s delusions.

Because the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies had at least several decades from which to select the “best” stories, and these subsequent anthologies are just taking the “best” from one given year, I naturally expected that these annual anthologies would be noticeably weaker, though hopefully still worthwhile (in much the same way that one would expect a team consisting of the top Hall of Fame baseball players to be able to soundly defeat one year’s all-star team). But as far as Nebula Award Stories Eleven goes, I’d say I enjoyed the average story in this anthology at least as much as and probably slightly more than the average story in the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies.

When I think about the handful of stories in the Science Fiction Hall of Fame anthologies that most impressed me or that I got the most out of, it’s true none of the stories in this anthology quite reach that level. So it does not have quite as high highs. But by an even greater margin it does not have as low lows. This anthology has none of those insufferable Tolkien-type stories where people in the future or on other planets have somehow regressed to some bizarre state where they have princesses and castles and macho warriors fighting dragons and such. Nor are there any inscrutable surreal—or I suppose today we’d say postmodern—stories where I struggled mightily to figure out what was going on.

For the most part these are stories that are understandable, that I enjoyed, and that made me think.

So I’d say this one’s a winner. Enough so to encourage me to check out the subsequent yearly anthologies from this series.

I love your review of San Diego Lightfoot Sue, one of my favourite short stories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much.

LikeLike